By Beth S. Pollak / All Photos Courtesy Jeff Schroder and the Field Museum unless noted

Did you know that T-Rex had enormous teeth up to a foot long? Tyrannosaurus Rex, also known as T. rex or T-Rex, was one of the largest meat-eating dinosaurs that ever lived. It’s also captured the imagination of fossil fans since its discovery in 1902.

For kids and families who want to learn more about T. rex and other dramatic dinos, #CampCaribu‘s ‘Animal Adventures’ Summer Reading category is a great place to start! Check out our favorite T. rex covers in the #CaribuApp, and learn more about dinos big and small! Explore prehistoric eras with fun facts and dynamic illustrations.

You also will find fictional tales that feature dinosaurs and other animals. Pick some dino books to read with your family in your next Caribu video-call. Enjoy all of the dino adventures in a virtual playdate!

To learn more about T. rex, we spoke to Jeff Schroder, Grainger Science Hub Facilitator at the Field Museum in Chicago, which is the home to the largest, best preserved T. rex fossils on Earth.

Field Museum Chicago

Jeff Schroder, Grainger Science Hub Facilitator

1) You’re an expert on Sue, the world-renowned T. rex. What’s new with Sue?

Sue is one of the most complete, best preserved and largest T. rex ever. We’re constantly learning new things about Sue! Sue was moved upstairs at the museum in 2018. The paleontologists at the Field Museum took that opportunity to study Sue and learn a little more.

When you think of Sue’s old skeleton [the original mount], the belly was kind of open. But in the new one, there’s these things coming across called gastralia. They’re not really ribs, but they look like ribs, so people call them ‘belly ribs.’ Scientists didn’t know exactly how they fit. From 2000-2020, they learned more they were able to put the gastralia on to the new mount for Sue.

Also, before that; the thought was Sue was probably about 7 tons; the gastralia added a couple of tons to the weight since the belly would have probably been bigger. So we’re thinking of a bigger animal that maybe wouldn’t have been as fast.

2) How old was Sue at the time of death?

We’re studying Sue’s age right now. Our paleontologists initially had done a study of how old Sue was when Sue died. It’s similar to how old a tree is. You can cut certain bones’ cross section or core, and count the rings to see how old they were. You want to take samples from different areas to back it up. You want reliability. The scientists, as they moved Sue, took samples from other parts of her body, and they’re going to cross-compare them and see how old Sue actually was. We’re thinking age 28-33, which would make Sue the oldest T. rex ever found, as far as life span.

One more bonus fact: they don’t just learn about Sue, from Sue. When Sue was discovered [in South Dakota] it was so significant that scientists collected some of the rock that was around Sue, and in it, they found little tiny shark teeth. So we know that little sharks were living together with Sue; that Sue was near water, and that it was probably a very wet environment.

3) Which other prehistoric fossils stand out in the Field’s collection?

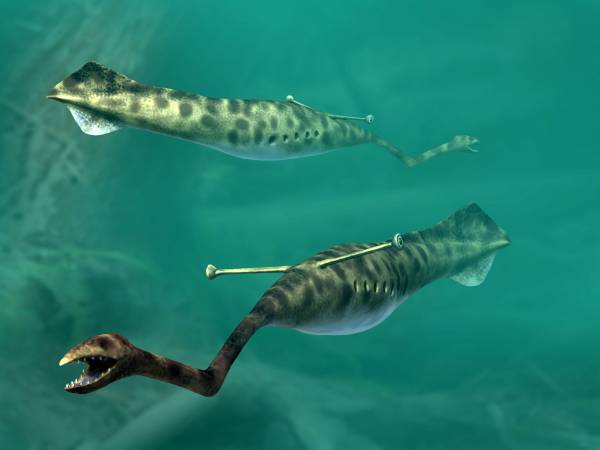

Illinois’s state fossil is the early fish called the Tully Monster (Tullimonstrum gregarian). It’s named after this guy who discovered the fossil in Illinois, Francis Tully. He was actually a pipe fitter who was an amateur fossil collector. He found it in the 1950s and brought it to the museum, and they were like, ‘We’ve never seen anything like this, we don’t know what it is!”

It had a little claw, a body like a worm, a tail like a squid, and eyes and stalks like a crab. They studied it extensively and discovered it was probably an early ancestor of lampreys, those blood-sucking fish that attach to other fish and drink their blood.

One reason we research is to figure out what these things are, where they came from, and where they headed. While not a dinosaur, even the scientists at the Field could not figure out what this was for 50-60 years. Using more than 2,500 specimens, only found in Illinois, they were able to look at all different angles of it. That’s why you need so many different specimens.

About 300 million years ago, at the time of the Tully, Illinois was right on the edge of what was at that time, an inland sea. The Tully would’ve been living in a shallow swampy area in brackish water right on the coast.

4) Do you have any additional favorite fossils?

One of my favorites is the megatherium, the giant ground sloth. We also have the Glyptodon, which is an early mammal. Picture an armadillo the size of a Volkswagen Beetle. Some of them have a long tail with spiked club on the end. It went extinct about 10,000 years ago, around the time that humans arrived in North America. Early humans crossing over to North American probably encountered these things!

5) What made the Permian Period unique?

The Permian Period was right before the dinosaurs evolved, and there were all sorts of weird creatures evolving and trying to establish themselves. It happened right before the Permian Mass Extinction, the worst mass extinction in the history of the earth. It was devastating to a lot of life on earth and really paved the way for the dinosaurs. But before that, you had all these weird creatures roaming around. They looked like dinosaurs but they weren’t. They were giant amphibians, unique odd creatures that you don’t see much of later on because of the extinction. It’s this blast in time of what could have been.

6) How can kids learn more about dinosaurs and fossils from home?

We have a lot of learning at home dino resources on our website. Check out our online SUE Tour. It’s an hour-long Sue talk that is live so you can ask questions, with trivia polls throughout. Also, look at the websites of local organizations that study fossils.

When things are stable post-COVID-19, you can go out and join digs with local organizations in your state and around your region. There might be a local fossil hunting club. If you have a place where you can go hunt fossils, make sure you have permission and a permit so you can go look around.

If kids want to see a real dinosaur, they can probably step out into their yard, because birds are dinosaurs. Not all dinosaurs died out. That’s one of the big myths. No, a few survived, they just happened to be small, had feathers, and could fly. And that’s what birds are today.

7) Why is it important for families to continue learning about prehistoric life even as we face difficult current events around the globe?

It’s important to look at how things happened in the past and how those impacted ecosystems. Studying the dinosaur fossils doesn’t just tell you about the animal in isolation. It tells you about the whole ecosystem were it lives, which is really pertinent to the earth as an whole.

Look at the history of viruses for example… Sue possibly died from an infection of little microorganisms, and those were traced to similar ones in birds today. There are connections to different things that we may be able to discover.

It’s fascinating to learn all the things we don’t know. It takes our brains away from rough stuff that we’re dealing with, and lets us investigate something inspiring that’s a welcome distraction and meaningful in its own right.

Read more about dinosaurs in the Caribu app! Download the app today so you can connect with your loved ones and share some more animal adventures. Learn, play, and color together in your next virtual playdate.

Beth S. Pollak is a writer and educator based in California. In addition to working with Caribu, she consults with educational organizations and EdTech companies. Beth has worked as a teacher and journalist in Chicago, New York, and San Francisco. She holds degrees in journalism, bilingual education, and educational leadership. In her free time, she enjoys hiking, biking, picnics, and dance.