El Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, is a traditional Mexican holiday that is observed annually on November 1-2. The holiday is a chance for friends and family to honor deceased loved ones and celebrate life. Many people across Mexico, Latin America, and the United States participate in memorials and festivities as part of the holiday’s events. Families and friends construct altars with offerings, photos, flowers, and incense to welcome the souls of those who have passed. Love ones gather to share, pray and reminisce together, and might visit gravesites to clean and decorate them with marigolds and gifts. In some communities, people dress up in costumes with skulls (calaveras in Spanish) painted on their faces.

Draw And Decorate

While in-person Día de los Muertos festivities might be quieter this year due to COVID-19, many are still decorating family alters and participating in online events. Join in the celebrations with Caribu’s drawing pages! Color calaveras and other traditional designs in your next Caribu Call. Connect with loved ones to share family stories and honor the spirits of those who have passed.

Explore Traditions

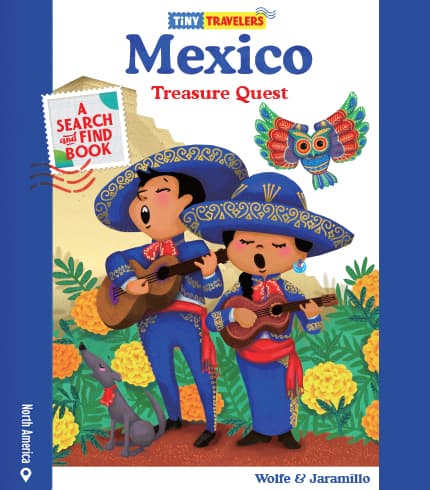

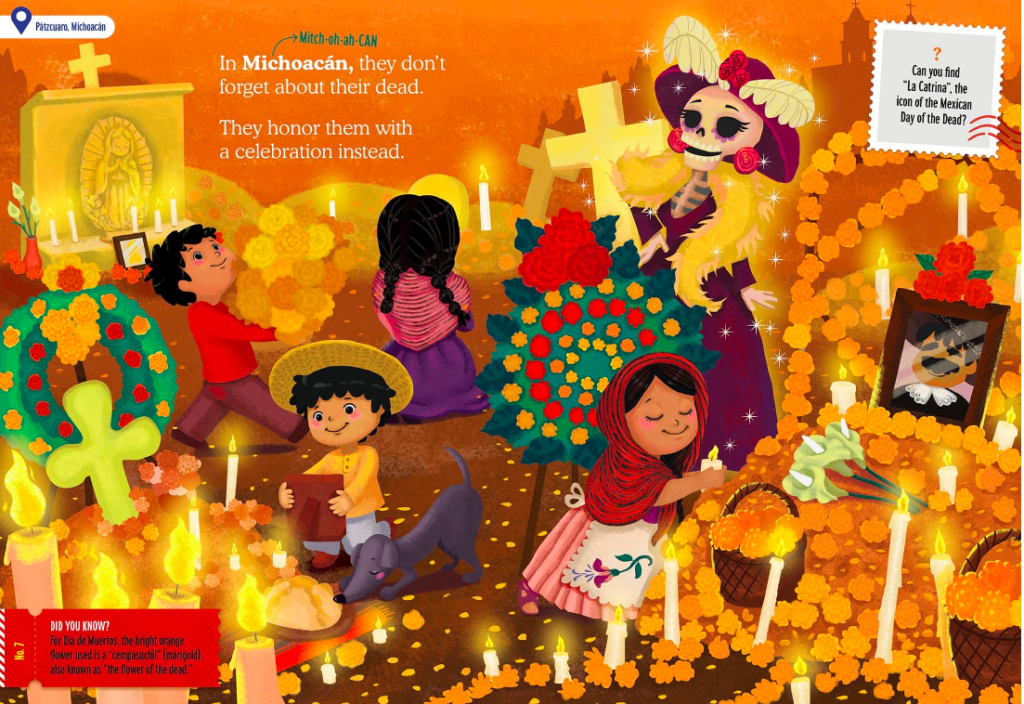

Plus, with Caribu you can read together about Día de los Muertos and many other aspects of Mexican life, geography, and culture in the book Tiny Travelers Treasure Quest: Mexico. Discover the highlights of this beautiful country, from its memorable mariachi music to its magnificent monuments. Enjoy an illustration of Día de los Muertos that highlights the holiday as it is celebrated in the city of Michoacán. Note the bright altars, colorful marigolds, family gatherings, and La Catrina, the symbolic skeleton.

To learn more about the history, rituals, and symbols of Día de los Muertos, read the below excerpt from National Geographic:

History

Day of the Dead originated several thousand years ago with the Aztec, Toltec, and other Nahua people, who considered mourning the dead disrespectful. For these pre-Hispanic cultures, death was a natural phase in life’s long continuum. The dead were still members of the community, kept alive in memory and spirit—and during Día de los Muertos, they temporarily returned to Earth. Today’s Día de los Muertos celebration is a mash-up of pre-Hispanic religious rites and Christian feasts. It takes place on November 1 and 2—All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day on the Catholic calendar—around the time of the fall maize harvest.

Altars

The centerpiece of the celebration is an altar, or ofrenda, built in private homes and cemeteries. These aren’t altars for worshipping; rather, they’re meant to welcome spirits back to the realm of the living. As such, they’re loaded with offerings—water to quench thirst after the long journey, food, family photos, and a candle for each dead relative. If one of the spirits is a child, you might find small toys on the altar. Marigolds are the main flowers used to decorate the altar. Scattered from altar to gravesite, marigold petals guide wandering souls back to their place of rest. The smoke from copal incense, made from tree resin, transmits praise and prayers and purifies the area around the altar.

Literary Calaveras

Calavera means “skull.” But during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, calavera was used to describe short, humorous poems, which were often sarcastic tombstone epitaphs published in newspapers that poked fun at the living. These literary calaveras eventually became a popular part of Día de los Muertos celebrations. Today the practice is alive and well. You’ll find these clever, biting poems in print, read aloud, and broadcast on television and radio programs.

The Calavera Catrina

In the early 20th century, Mexican political cartoonist and lithographer José Guadalupe Posada created an etching to accompany a literary calavera. Posada dressed his personification of death in fancy French garb and called it Calavera Garbancera, intending it as social commentary on Mexican society’s emulation of European sophistication. “Todos somos calaveras,” a quote commonly attributed to Posada, means “we are all skeletons.” Underneath all our manmade trappings, we are all the same.

In 1947 artist Diego Rivera featured Posada’s stylized skeleton in his masterpiece mural “Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park.” Posada’s skeletal bust was dressed in a large feminine hat, and Rivera made his female and named her Catrina, slang for “the rich.” Today, the calavera Catrina, or elegant skull, is the Day of the Dead’s most ubiquitous symbol.

Food Of The Dead

You work up a mighty hunger and thirst traveling from the spirit world back to the realm of the living. At least that’s the traditional belief in Mexico. Some families place their dead loved one’s favorite meal on the altar. Other common offerings:

Pan de muerto, or bread of the dead, is a typical sweet bread (pan dulce), often featuring anise seeds and decorated with bones and skulls made from dough. The bones might be arranged in a circle, as in the circle of life. Tiny dough teardrops symbolize sorrow.

Sugar skulls are part of a sugar art tradition brought by 17th-century Italian missionaries. Pressed in molds and decorated with crystalline colors, they come in all sizes and levels of complexity.

Drinks, including pulque, a sweet fermented beverage made from the agave sap; atole, a thin warm porridge made from corn flour, with unrefined cane sugar, cinnamon, and vanilla added; and hot chocolate.

Costumes

Day of the Dead is an extremely social holiday that spills into streets and public squares at all hours of the day and night. Dressing up as skeletons is part of the fun. People of all ages have their faces artfully painted to resemble skulls, and, mimicking the calavera Catrina, they don suits and fancy dresses. Many revelers wear shells or other noisemakers to amp up the excitement—and also possibly to rouse the dead and keep them close during the fun.

Papel Picado

You’ve probably seen this beautiful Mexican paper craft plenty of times in stateside Mexican restaurants. The literal translation, pierced paper, perfectly describes how it’s made. Artisans stack colored tissue paper in dozens of layers, then perforate the layers with hammer and chisel points. Papel picado isn’t used exclusively during Day of the Dead, but it plays an important role in the holiday. Draped around altars and in the streets, the art represents the wind and the fragility of life.

Day Of The Dead Today

Thanks to recognition by UNESCO and the global sharing of information, Día de los Muertos is more popular than ever—in Mexico and, increasingly, abroad. For more than a dozen years, the New York-based nonprofit cultural organization Mano a Mano: Mexican Culture Without Borders has staged the city’s largest Day of the Dead celebration. But the most authentic celebrations take place in Mexico. If you find yourself in Mexico City the weekend before Day of the Dead this year, make sure to stop by the grand parade where you can join in on live music, bike rides and other activities in celebration throughout the city.

You can read the original article in National Geographic.

Logan Ward, Top 10 Things To Know About The Day Of The Dead, October 26th, 2017, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/destinations/north-america/mexico/top-ten-day-of-dead-mexico/.